Preserving Rare Livestock Breeds

In the U.S., when most people think dairy cattle, the black and white Holstein usually comes to mind. When they think beef, Angus is usually the first cattle breed out of their mouths. Common horse breeds are the Quarter Horse and Thoroughbred, and popular sheep breeds are the Dorset and Suffolk. All these breeds are popular for specific reasons: Holsteins give the most milk, Angus are known for good meat quality, Thoroughbreds are the super-athletes of the horse world, and Quarter Horses can do just about anything. (I am a bit partial to Quarter Horses, so please excuse the hyperbole — but it’s true.)

But what about rare breeds of livestock?

The American Livestock Breeds Conservancy (ALBC) was organized in 1977 to preserve rare breeds of livestock in the U.S. Although having the bragging rights to raising a rare breed of animal can be reason enough for some people to pursue this hobby, the primary reason such a conservancy exists is to help preserve biodiversity.

When most people think about species extinction, animals like the elephant, cheetah, and mountain gorilla tend to come to mind. Usually the thought of a farm animal going extinct just doesn’t register, and it’s certainly not as glamorous. However, preserving threatened livestock breeds has recently become a global concern. The Food and Agriculture Organization within the United Nations reported in 2007 that 20 percent of the world’s 7,600 livestock species were at risk of extinction. That’s a huge chunk of the gene pool.

How exactly, then, do livestock go extinct? Some, like the Santa Cruz sheep, were purposefully eradicated. Almost.

Living only in the Channel Islands National Park off California, in the 1980s, eradication attempts on the Santa Cruz breed were made in an effort to protect the park’s flora. The sheep population dropped from more than 21,000 to about 40. Fortunately, this is a fairly extreme case. The more common reason for dwindling numbers is simply competition. The common breeds of today’s livestock are the highest producers of whatever they are used for: namely, the best milkers or the biggest muscling for meat. If a farmer only has a limited amount of land, to make a living, he needs animals that can produce the most on what he has to give them. Such is the name of the game in agriculture.

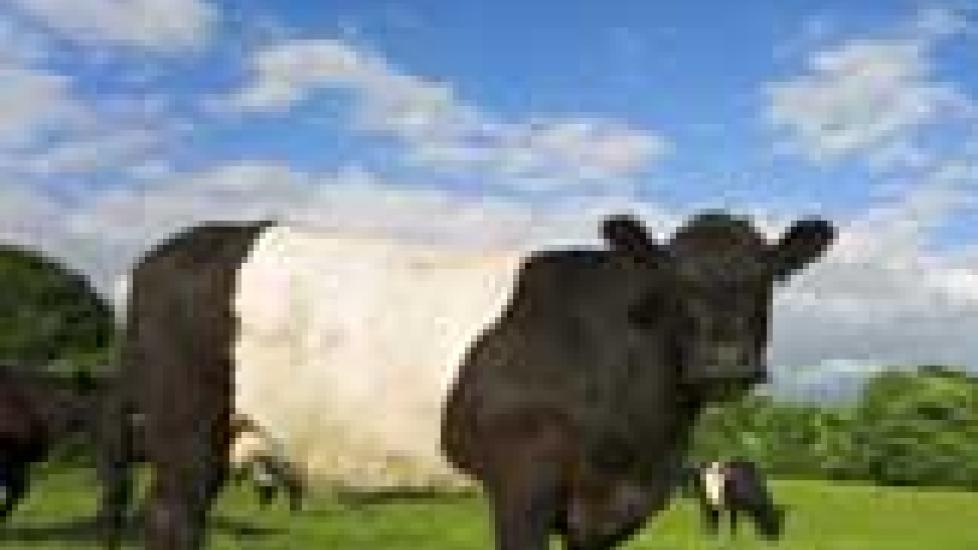

I’ve never been to a dairy that has the breed Milking Devons. Or a hog farm with the Gloucestershire Old Spot Pig. But I have seen a farm with Tunis sheep, a lovely orange-colored sheep that gets fairly large, and they are extremely personable, as well as a farm with Jacob sheep, a small breed with black and white spots that are “polycerate,” or multi-horned, meaning they can grow two horns on each side (I call these extra handles). I’ve also been to a farm that raises Belted Galloway cattle, or as I call them, Oreo cows, because they are black at both ends with a white “belt” in the middle.

Visiting these farms is always neat and sometimes a challenge. Some of the rare small ruminant breeds are quite flighty, making catching them sort of a comedy to the outside viewer. Acting very much like a wild prey species, some of these rare sheep breeds are extremely susceptible to stress and require far smaller doses of anesthetics than their common counterparts.

People who raise these breeds keep immaculate breeding records of their animals and can sometimes trace lineage back generations, making you realize just how small some of these gene pools really are. Larger operations help breeds through more advanced technologies like keeping frozen semen and even harvesting and storing frozen embryos.

If the loss of species is a little depressing, take heart. On ALBC’s website, there are lists of recovering breeds, so intervention appears to be working for some.

As with most things, the initiation to make a change is awareness. If you’re interested in learning more about these threatened breeds of livestock, take some time to peruse ALBC’s excellent website. You might even find a local event like a Rare Breeds Show or Livestock Expo to attend.

Dr. Anna O’Brien

Image: (Belted Galloway Cattle) Dave McAleavy / Shutterstock