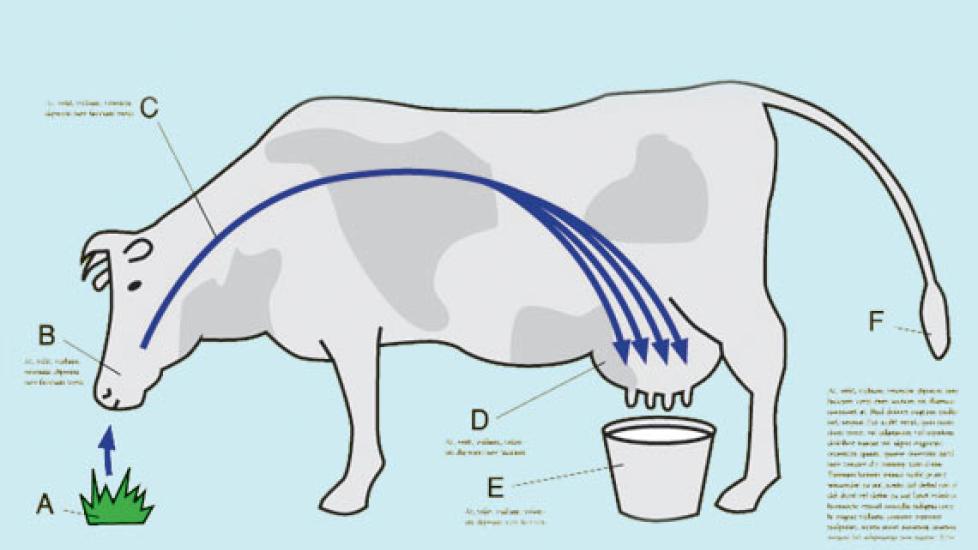

How a Cow Works

Today I feel the burning desire to share with you the science behind the magnificent beast that is the cow. They really are quite modest creatures, standing there in the field so sedately chewing their cud, while inside, they are factories of microorganisms working away non-stop at breaking down grass and grain, producing volatile fatty acids, and of course, methane. What fascinating (and gassy) creatures!

To begin, it is true that cattle (also called ruminants) have four stomachs. To look at these stomachs anatomically, they sort of appear like one giant odd-shaped sphere, but there are actually four distinct spaces within this sphere that constitute four different parts of the digestive tract. Let’s investigate this unique anatomy in a little more detail.

As a cow grazes, she is primarily consuming cellulose, the building block of plant matter that is difficult to digest. Cows swallow large chunks of grass at a time and then later, usually while laying down, they regurgitate this grass back up in order to re-chew it a second time. This process is called ruminating. This allows the grass to be as physically broken down as possible by the mechanical action of chewing before entering the digestive tract. Salivary enzymes mix with this chewed grass, beginning the chemical digestive process even before the grass hits the stomach.

Once swallowed a second time, the grass enters the first of the four stomachs, the rumen. This is the largest of the four stomachs and can contain up to 50 gallons of fluid in an adult cow. The rumen is basically a large fermentation vat. It is filled with “good” bacteria, protozoa, and yeast that are permanent hitchhikers within the cow in a symbiotic relationship, since they are the ones responsible for breaking down the cellulose. In fact, when cows become sick, oftentimes these microorganisms die off. This can make the cow even sicker, and we need to force feed her microbes from a healthy cow to re-populate her gut — sort of like when we eat yogurt with live cultures whenever we have diarrhea or take antibiotics.

Anyway, let’s take a quick step into biochemistry just for a moment. You may wonder how the heck a large animal like a cow gets any energy from grass. The answer lies in these microbes. As they digest the cellulose by way of fermentation, their metabolic pathways produce chemicals called volatile fatty acids (VFAs). The cow uses these VFAs as a primary source of energy. There are three VFAs produced: acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid. These VFAs in ruminants and other large herbivores play the role of glucose in monogastric animals like humans, cats, and dogs.

So, back to the anatomy. Once grass is in the rumen, it mixes with the other ingesta that is there. As it mixes around in the rumen, it will make its way to the reticulum, the second stomach. The reticulum is a much smaller out-pouching in the frontal aspect of the rumen. This stomach aids in the mixing of digesta but also acts as a catch area for foreign bodies, like stones, twine, or bits of metal such as nails that a cow may pick up while grazing or eating from a trough. A condition in cattle called “hardware disease” occurs when a piece of metal is swallowed and perforates the reticulum. Sometimes, the rumen and reticulum are referred to as a single entity: the reticulorumen.

Next, the ingesta enter the omasum. This, in my opinion, is the weirdest of the stomachs. A small round organ, the inside of the omasum has many thin leaves of tissue that help absorb water and help filter large particles back to the rumen.

The fourth stomach is the abomasum, also known as the “true stomach.” Here is where digestive enzymes made by the cow herself act to digest proteins and carbohydrates, much like our own stomach acts. After this last digestive step, food passes to the intestines, where most of the absorption of nutrients and water occur.

Sheep and goats are also considered ruminants (classified by size as “small” ruminants) and have digestive systems exactly like a cow, except of course their rumens don’t hold 50 gallons; more like two. Other grazing animals such as deer are ruminants as well.

Horses, on the other hand, have to be complicated and not adhere to the “if thou art an herbivore, thou shalt have a rumen” doctrine, instead being “hind gut fermentors” with a large colon that tries to do what the rumen does, but ends up being slightly less efficient. However, despite the inadequacies of a horse’s digestive system, I will forgive them for this one simple fact: they do not ruminate, which I believe would greatly decrease their elegance.

No offense to cattle, but seriously. A burping horse? I can’t quite imagine that in the show ring.

Dr. Anna O’Brien

Image: Almog Ziv / Shutterstock